Printmaking satisfies the scientist, historian, and all those who thirst for meaning in our fast-paced society but to the dedicated onlooker questions about “What is a Print“ continue to dominate the discussion.

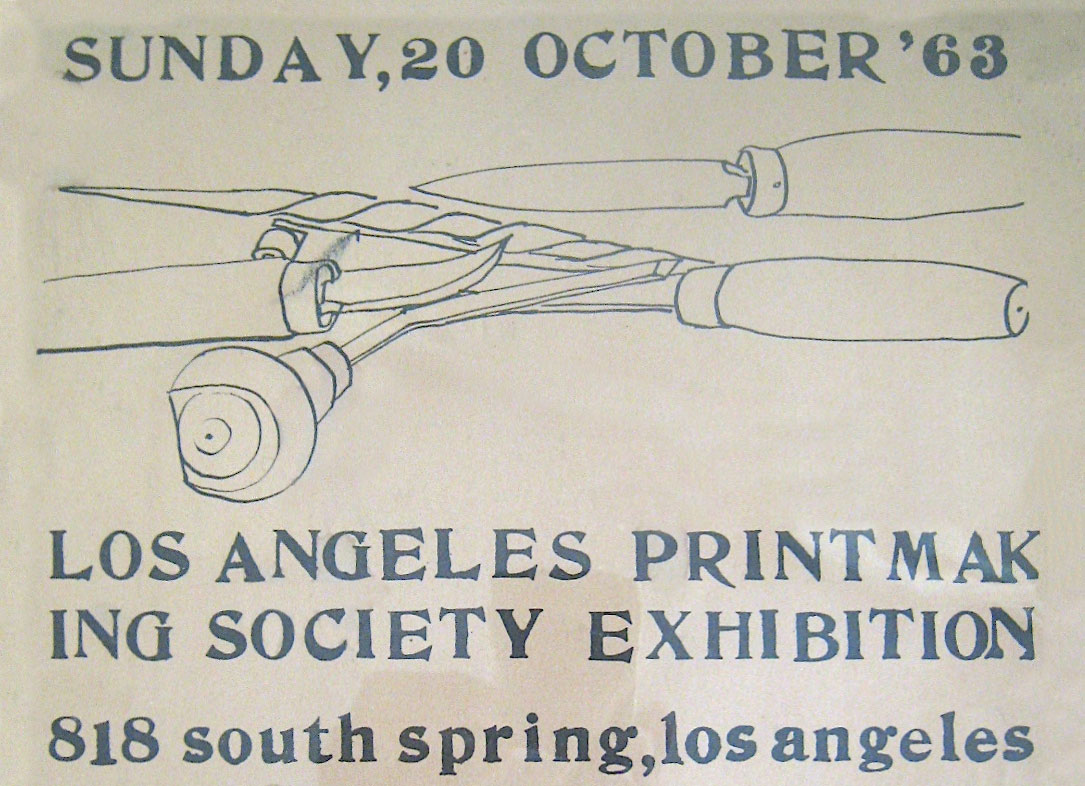

Since photography and Walter Benjamin’s treatise on reproduction, identifying a print has become worrisome. Sure, it was much easier back then. One could identify an etching by the rich coarse lines and embossed plate mark raised onto the edge of the paper or a lithograph by the flatness and unpixelated soft tones created by the lithographic crayon. Today every major print venue grapples with the inclusion of digital / photographic imagery.

But, where else in today’s polarized society can one find civility amidst such a broad range of topics? Print exhibitors expose the ongoing debate on methods and materials and the speed by which technology shapes the arts, a concept enshrined by noted critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin in his 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Photo-Mechanical Reproduction.”

While it has always been the job of moderators of the practice to understand the driving concepts behind the art as well as the specific techniques employed, some print competitions challenge new directions within the practice, believing that innovative digital techniques do not always serve the best interest of the print medium. Things are a changin’ in the art-digital arena, as Walter Benjamin had anticipated. The preponderance of digital techniques has forged an army of detractors who have resisted inclusion of purely digital printmaking out of a respect for the past and/or simply because the digital medium appears a diminished aesthetic experience. As Walter Benjamin observed, “The conventional is uncritically enjoyed while the truly new is criticized with aversion” (Benjamin 1969, 14.).

Emotional responses directed towards artists who employ new digital techniques are evident during every exhibition. The seeds of discord develop because digital elements exist within a closed catalog of invisible files and virtual algorithms, instantly accessible, but lacking human variations. Benjamin’s work references the quandary and ongoing angst of art in the age of mechanical reproduction by asserting that even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be. Here, Benjamin speaks of authenticity, the prized but elusive element of the original print. He anticipated the artistic conflict present in digital technologies when he wrote about photography’s impact on the printed image in 1935. Benjamin understood that the future of art will be transformed as new technologies develop, changing the very notion of how we appreciate art. While spectators enjoy images presented in a gallery setting, emotional issues play out as artists ponder their own physical involvement and emotional connection to the final product. Arguments about digital printmaking removing the uniquely human touch by eliminating missteps are commonplace.

The resurgence of the woodcut print illustrates the artist’s attraction to direct involvement and ultimate control attained by cutting directly into wood, a decidedly analog approach to artmaking (Sax 2017). Richard Hricko, retired university professor and founder of Crane Arts in Philadelphia, creates large -scale relief prints using a laser cutter. His digital laser relief print “Remnant” is one example of the everchanging print medium. During the opening day of an exhibition in Boston a small crowd gathered in front of Hricko’s large format print labeled “woodcut”: an image that confused the astute onlookers. His laser woodcuts are not typical of high contrast prints produced in the traditional relief style. The laser cuts a full range of halftones into the Baltic Birch plywood surface each incredibly shallow but well defined. The compositions are reminiscent of nineteenth century gravures. Richard ‘s latest project involves integrating seven laser woodcuts into one cohesive narrative, each wood block measuring 2×4 feet. Richard begins his process by arranging grasses, twigs and objects onto an 11×14 flatbed scanner. After developing a high resolution scan he travels to a community workspace placing the birch plywood block into an enclosed station for three hours or more while the laser burns and smokes lines into the plywood. Printing and rolling ink over the surface without filling in the lines is the real challenge requiring the talent of a master printer, a skill that has taken Richard years to perfect.

Eric Avery, South Texas printmaker and retired physician, created a notable contrast to the ever-present digital prints displayed at the recent exhibition.

Avery’s interactive woodcut print, Neurogenesis, embodies the brain’s activity as a neuron-producing healing agent. Show organizers act as caretakers during the exhibition to water and nurture the print as seeds germinate and grow from the fibers of the paper. The membrane simulates how the brain works to counteract trauma. The print exits its role as wall display and enters into a life cycle, as spikes of grass develop on the surface and eventually change into blacks and whites, as embedded neurons wither and die. The print fully engages the audience’s senses by offering a new approach to traditional methods in direct contrast to digital work, which is perceived as a closed system despite its vast catalog of responses.

Printmaking is ground zero of this struggle, being played out in every competitive print exhibition throughout the world. Digital methods are criticized because content is likely culled not from experience but from a pool of information derived from virtual algorithms. The ubiquity of digital techniques means that at any moment the public can gain access to the process and declare artistic relevance. As printmakers cope with the influx of new processes, many have welcomed variations to traditional approaches and find a competitive spirit rising as they explore digital processes, even as many print competitions still refuse digital entries—a perceived challenge to the status quo. Do digital techniques degrade the quality of the image?

A teachable moment occurred after the close of one of the exhibitions when an artist refused to pay return shipping for his digital print that had been included in the exhibition. The cost of shipping the print exceeded the artist’s perceived value of the artwork, further complicating the issue of reproduction of the computer-aided image. Walter Benjamin knew that certain rudiments of artistic practices will fade, and here we are seeing an example of the depletion of the print’s value—or what Benjamin referred to as the “aura” of the artwork. In Benjamin’s mind, the “aura” is power or the print’s accumulation of supportive information defined by society and experienced by the viewer.

Having to set standards for artists to follow, force print competitions to pose restrictions on submissions that suppress artwork which may in fact herald the next new change in direction. In keeping with printmaking’s tradition of offering the most advanced modes of image production, some venues have opened the floodgates to accommodate all modes of digital print production. Although there are many print venues that expressly refuse computer-generated entries, hybrid compositions in their many forms are typically allowed access. To discerning printmakers, the walk through the gallery can be disturbing as well as enlightening. Confusion often arises when the process becomes hidden from the experienced onlooker—when the technique used to create the print is not so obvious.

Artist Michelle Martin, a frequent contributor to national print competitions makes prints that straddle the old and new, speaking directly to the quandary facing printmakers today. Martin tests her audience’s ability to accept her way of co opting the characteristic lines and strokes she plucks from Victorian illustrations and 18th century wood engravings. Distinct features of engraved lines are digitally stitched into her compositions. Hers is a clever balance of the use of the human hand manipulating digital elements to create dramatic landscapes. However, only upon close examination is the human hand visible in the print-work. The real work lies in the obsessive pixelating process of image building, a bit-by-bit construction of a complex composition. Michelle is a digital collage maker, taking scans from books, and clip art; she describes her process as “restoring” the completed image. Well-versed in Photoshop techniques, and using as many as 188 different layers, she creates files that can grow to one gigabyte. She considers the inking and hand wiping of the plate an all-important final step in the process.

Artists are finding new ways to integrate digital processes into their artwork that are not so obvious to the well-trained eye. It is perceived by many that when the print is devoid of human qualities, it is seen as a temporary, ungrounded exercise, but responsible gatekeepers are learning more about digital media’s effects on art-making and human nature, and as they scrutinize performance in the field, they understand the pathway to creativity must remain open.

Robert Tomolillo started his career during the burgeoning of the print workshops in the late sixties. He worked at Impressions Workshop in Boston, and at The Printshop in Amsterdam, Netherlands. He holds a B.F.A. from Umass, Amherst, and an M.F.A. from Syracuse University. A faculty member at the F.A.W.C. in Provincetown, MA. and member of the Boston Printmakers since 1983, his lithographs are included in collections here and abroad. In 2008 he exhibited his prints in 15 national and international print competitions. He has written several articles on printmaking with a feature this past year in the Print Alliance Journal “Art and Politics”. A contributer to Thieves Jargon, Literal Minded and Orange Alert Zines he was the 2009 co-winner of the first Dayton Arts Museum International Peace Prize for his digital “Think Peace” poster design.