Mokulito is an amalgamation of the words “Moku” (Japanese for wood) and “Lito” for the lithographic process. Applying the same principles of the traditional stone-based lithography that oil and water don’t mix, in Mokulito, plywood is used as the substrate to prepare the plates for printmaking. The same oil or fat based (oleophilic) liquid or solid drawing materials are used to draw or paint the image onto the wooden plate. Then the open areas are treated with Gum Arabic to maintain their water wettable (aquaphilic) property. From here, the process deviates somewhat from the stone litho, where the drawn image is etched into the stone with acids before the image itself is removed from the stone slab. In Mokulito, the image has to remain on the plate which should now “rest” for at least three days to a week before the actual printing process can commence.

This printing process was originally developed in the 1970s by Professor Ozaku Seishi of the Tama Bijutsu University in Tokyo, Japan. Unfortunately, he has provided very little documentation on Mokulito and also when the process was later adopted by the Polish artists Józef and Ewa Budka, detailed information remained scarce and superficial. Around the middle to the end of the last decade, Mokulito became increasingly popular with printmakers as an innovative, non-hazardous, litho-like printing technique.

Similar to stone lithography, a large number of variables are involved in the process: the type of plywood, the various drawing materials, and the processing and printing process. As a person with a technical education, I approached the matter in a systematic way to separate wheat from the chaff on information available in the public domain. The objective was to eventually provide certain guidance to interested printmakers which resulted in my brochure “Mocu-Docu”, meanwhile in its second edition. This write-up is not meant to be a sure-fire “cookbook” and shall also not replace workshops, where one can not only become acquainted with the process, but also can receive tips and tricks from the experts.

The selection, type and preparation of the plywood are in my view the most important element in the entire process – and probably the most unpredictable one. Not only can you choose from a wide range of different wood types; you can never be certain what production processes, handling, and storage conditions the wood has experienced – all of which have some kind of influence on the Mokulito process.

Early publicly available information conveyed the impression that only hardwood plywood would be suitable to produce satisfactory prints. However, the availability of different plywood types is often dependent on the location of your supply store. They may offer alder, ash, oak, beech, birch, elm, linden, luan, maple, poplar, walnut … so what wood to use? So several test series were conducted with the plywood which is generally available in Europe which were ash, beech, birch, elm, maple and poplar. Some precious or exotic wood plywood types, like cherry and mahogany, are generally prohibitively expensive and have therefore not been included in my test sequences. As it turned out, every wood type will show a different behavior and will have an individual and particular effect on the prints. In addition, when I started to expand my tests to soft wood (pine, fir) and other wood derivatives (oriented strand board, particle board) it became evident that the Mokulito process works essentially on any wood and even wood-containing substrates.

As a general rule, any wood with a high resin content (all softwoods but especially pine) will show the wood grain from the first print onwards. Hardwoods will show the wood grain on the prints either after a few prints have been pulled or not at all. Birch and maple especially will maintain a close-perfect white on the “open” areas. The number of good prints to be pulled also depends on the type of wood which ranges from just a few (5-6 with poplar) to 20+ (with birch, maple).

The next element in the process are the drawing materials. While essentially all fat, wax or oil containing materials work, tests with individual products have shown that liquid products result in better and larger numbers of good prints. Solid drawing materials such as oil pastels, litho sticks and crayons will work in principle, but the drawings tend to separate and be lifted from the plywood plate during the inking up and printing process. In contrast, liquid drawing materials (“tusche”) and oil based markers will permeate the plywood and will therefore provide more and better prints.

After the drawings have been made on the plywood and allowed to properly dry, the plate is dusted with talcum powder and subsequently etched twice with Gum Arabic. Experience has shown that the plates should “rest” for at least three days – a longer period does not harm. But attempts to print the plates earlier leads to inferior results, as the Gum Arabic etching process requires a certain time.

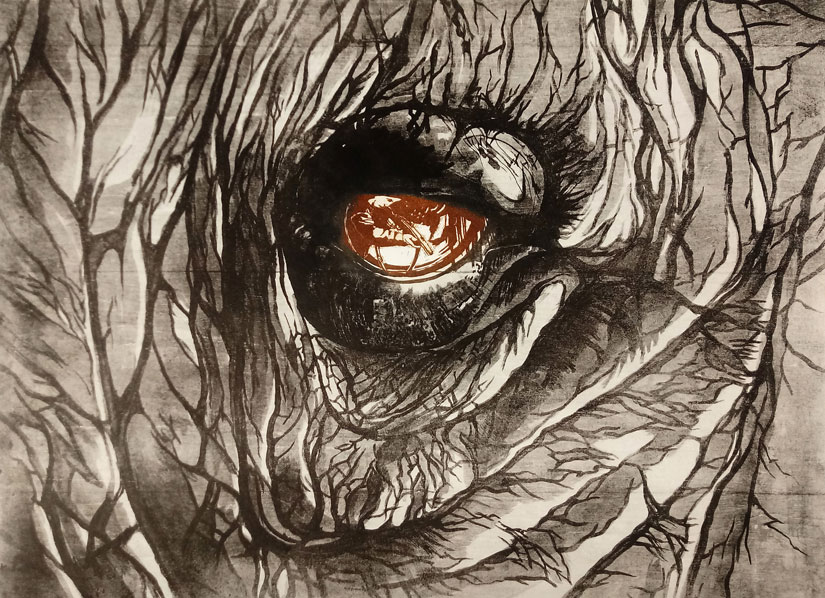

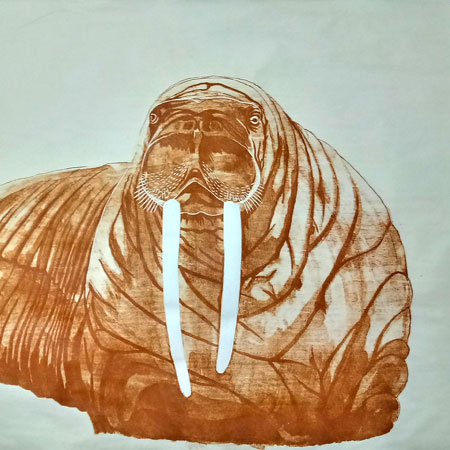

One advantage of Mokulito versus stone lithography is the possibility and option to combine the flat, lithographic print with the woodcut process all on the same plate. The cut-out areas will result in a distinct white of the paper in contrast to some plate tone of the remaining uncut plywood plate.

The type of (oil based) printing ink and paper are essentially the same as for stone litho although the ink should be somewhat “longer” (i.e. thinner) but not soupy. Water mixable/soluble printing inks will not work at all. Rolling ink up with an industry type foam roller and keeping the plywood plate wet at all times during the inking process is essential. Although I have printed on anything from a 9 gr Tengucho to a 350 gr Hahnemühle and anything in between, I find that best results can be achieved with a medium weight (say 190 gr) well sized, smooth paper such as the Hahnemühle 190.

For those intaglio printmakers owning or having access to a printing press, it’s good news. You can pull prints from Mokulito plates without the need to invest in or have access to a lithographic press. The press setup will be somewhat similar to relief printing i.e. you will need runners to keep the press level at the plywood thickness. The pressure setting is much less than for intaglio but somewhat more than for relief. I do not use a blanket but a flexible plastic sheet similar to the tympan in stone litho printing. While I have tried many ways to pull prints without the use of a printing press, the only viable alternative is the use of a steel ball baren – and even those prints are coming out, well, just so-so…

Multiple color printing is as much of a challenge in Mokulito as it is in stone litho due to the paper registration requirements of printing separate and individually colored plates. Alternatives are the techniques of à la poupée (inking up separate areas of the plate with different colors); the use of blended rolls; chine collé or post-print hand coloring.

In the past years, I have participated in several open calls and I am glad to say that I have succeeded with my Mokulito prints in exhibitions in the Americas, Australia and Europe. My prints often (but not exclusively) portrayed endangered animals which are related to my effort to draw public attention to the increasing threat of our fauna due to poaching, loss of habitat and climate change.

During the years of learning Mokulito printmaking, I have received valuable and unselfish support, advice and information from printmaking artists around the world, especially from Ariadna Abadal, Danielle Creenaune and Oksana Stratiychuk. My sincere thanks and gratitude is going out to them. In appreciation of this supportive attitude, I want to reciprocate by inviting interested printmaking artists to contact me for a copy of my Mokulito brochure – analog, if you reside anywhere with a decent postal service or digital, should this not be the case.

After an earlier career in the international petroleum business, Bernhard Cociancig graduated from the Vienna Art School in Printmaking, Graphic Design, Painting & Process. He enjoys international travel as artist in residence at least once a year, and has a love for working in different studios with other artists and in other countries. His practice encompasses essentially all printmaking techniques of relief, intaglio, and screen print but his focus is presently on Mokulito (lithography on wood). As an engineer, he relishes the challenge to understand and to master this process. After compiling results from years of numerous tests, Cociancig is still occasionally surprised by unexpected results– and is then spurred to understand and replicate it in a predictable way. He focuses on printmaking techniques which use which non-hazardous and cheap, renewable materials like plywood. He applies the same principle to metal plates for intaglio printmaking, using electro etching to prepare copper, zinc, steel and aluminum plates.

Cociancig also engaged with physically and mentally challenged people, volunteering as an art therapist. He is a member of the Board of the Vienna Art School as well as the Union of Professional Artists, where he networks with EU and international artists